Is Arabica in endanger of extinction?

All words by

Anton Louw

In the last few weeks, popular media picked up on a scientific article looking at the threat of climate change to the Arabica coffee plant. The word

‘extinction’ grabbed my attention; it may have made you splutter your morning brew as well. Depending on which article you read, the situation is not as dire as it may sound – we may not need to switch to tea anytime soon. But, the threat is noted and a worst case scenario is not impossible. In fact, very similar events have happened before –both in the natural history of the world, and in commercial agriculture.

The news articles were concerned with research done by the Royal Botanical Gardens of Kew. The project that produced the paper was led by

Dr Aaron Davis – who prefers his single estate roast with milk in morning, but medium-long black for the rest of the day. “Our study was focused on wild (indigenous) Arabica in Ethiopia and South Sudan.

Wild arabica in the south of Ethiopia

Wild arabica in the south of Ethiopia

The predictions show a negative impact across different emission scenarios for wild Arabica.” The direst predictions calculated that it would only be viable in 0.3% of its current range. They admit, this just looks at climate scenarios – it doesn’t account for things like the already fragmented habitat, changes in flowering or the role of birds in seed dispersal. While most of us don’t drink wild Ethiopian ‘forest’ coffee regularly, the threat to us lies in the genetic reserve that it provides commercial crops. But, more on that later.

The reason a warmer climate is a threat, is due to Arabica’s preference for tropical highlands. As climate changes, this vertical layers shifts with it. If you recall Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth, he showed this with malarial mosquitoes being able to take hold in cities such as Harare and Nairobi – formerly too high and cool for them.

Such extinctions have taken place at numerous times in the Earths’ history. In Europe and Asia, mountain ranges tend to run from east to west. During previous Ice Ages, advancing cold expanding from the Arctic effectively crushes species against mountain ranges from the Pyrenees to Himalayas as plants favouring a warmer climate cannot flee over the cold high peaks. However in Africa and the Americas, they tend run north to south and so these places enjoy much higher plant diversity as extinctions have been less. This is possibly why many domesticated plants come from the New World.

The problem now with a warming climate, is that wild Arabica is already at the end of its range. Under the worst scenarios, it can’t climb higher and it can’t flee to a cooler north either – blocked by the lowlands of Sudan and the Sahara. Should these scenarios come true, we would be left with very little genetic diversity amongst the remaining Arabica plantations around the world.

In Ethiopia itself, “optimum cultivation requirements are likely to become increasingly difficult to achieve in many pre-existing coffee growing areas, leading to a reduction in productivity, increased and intensified management (e.g. the use of irrigation), and crop failure,” explains Dr Davis. To counter this, he suggests improving the existing coffee reserves and then finding more climate resistant varieties, or even using a different species, such as Robusta.

The implication for the global coffee industry is that in the event of a disease or pest, there is very little genetic diversity amongst cultivated coffee to resist it. One bug could wipe it all out, and climate change increases the chance of such a bug appearing. Yet, without that wild reserve, there’s nowhere to go to look for resistant plants. If it were to occur, we’d be very lucky to escape a change in flavour from all this, and the least that could be expected is a price shock.

There are two pertinent examples of this from recent history.

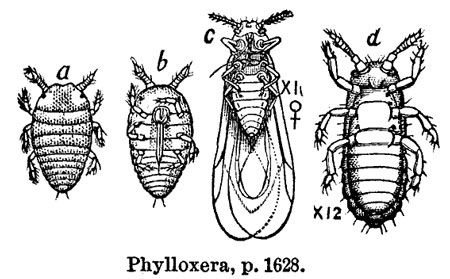

The first comes from wine, where a North American root mite called phylloxera escaped into Europe and decimated vineyards. Native American vines, which aren’t great for wine, provided resistant root stock onto which almost all wine grapes are grafted onto today. While the wine industry was saved, the debate raged as to whether pre-phylloxera wine was superior.

The little root mite that crippled the European vineyards.

The little root mite that crippled the European vineyards.

The second warning comes from bananas. Bananas don’t produce fertile seeds and are propagated by taking part of the root system, or even part of the stem and transplanting it. This means bananas have extremely low genetic diversity. If you enjoy the taste and creamy texture of bananas now, you would have loved to have tasted the current Cavendish banana’s predecessor – the Gros Michel. Panama disease effectively wiped out this strain in the 50’s and 60’s and the Cavendish, which showed resistance as well as a better shelf-life, took its place. While there are some diseases that threaten the Cavendish, it doesn’t face immediate collapse. Yet, there isn’t another banana around at the moment that can replace it.

So what are the implications for coffee? We are yet to see a global pandemic amongst coffee, but it’s not impossible. The key is to ensure that we have a genetic library to go to, and the best place for this is its natural habitat – as you know with your beans, viable coffee cherries don’t store well. The good news is Dr Davis and his associates are working hard to ensure these genetic reserves are protected, and exploring the world – from West Africa to Australia to find new coffee species. And although they are turning up, their usefulness to us is still being tested. In the meantime, enjoy the Arabica as you like it, but also get out there and taste as many obscure things as you can – it may be a privilege not available to you in the future.

So we can breathe a sigh of relief for now, but it does make you want to go out and find some delicious Ethiopian coffee while you still can :)