Everyone’s got their favourite blend. A “house blend” and themed blends are a staple for coffee roasters and their customers. These blends are synonymous with pleasing lattes and punchy flat whites. Typically, the cups of coffee you’re buying from your favourite cafe are a blend of coffees from different origins, with different processing methods and ideally, these would be communicated with you. There is certainly an art to blending and blending for an espresso that holds up to milk. It is a big part of the coffee industry and shouldn't be ignored, even if it has a less than stellar reputation in the specialty coffee industry, mostly because of big, commercial practices.

What is a Blend? What is a Single Origin?

Much like wine, where there are “red blends” and also single-varietal only options like Malbec or Pinotage or Sauvignon Blanc, there are coffee blends and single origin coffees. A blend would be a mix of different coffees that could differ in their processing, origin or varietal. For example, a washed Colombian Typica blended with a natural Rwandan Red Bourbon. A single origin would be a coffee from a single producer, a single processing method or a single varietal, for example, a washed Kenyan SL28. (NOTE: varietals can however be mixed at farm-level and the lot will still be called a “single origin” because the coffees are processed together and grown in the same terroir). A blend is made up of multiple single origin coffees.

Why Blend?

There are a number of reasons why coffees are blended. To create a “house blend” type of blend, both price of green coffee and flavour have a role to play. Often, a cheaper coffee will be the base of the blend and it will be blended with slightly more expensive coffee for their positive flavour characteristics, but the cheaper coffee allows a greater volume at a better price.

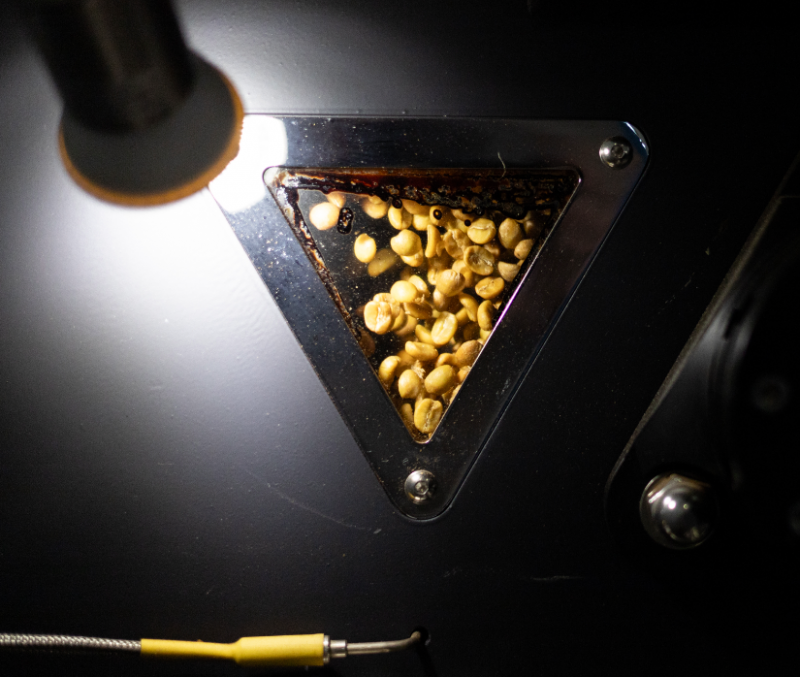

Blending can also be used to hide defects in a coffee, whether it be aging green coffee or defects due to inferior processing or production. Throwing a better coffee in with a poor quality coffee is a good way for roasters to get the best out of a lower quality bean.

For our third-wave specialty coffee consumers, a high-end blend is a curated flavour experience. Blending exceptional-quality coffee allows manipulation of the flavour experience.For example, in coffee competitions, if the competitor has chosen a coffee with a flavour profile that they love but they find the acidity to be too wild, they can blend it at a low ratio with a lower acidity coffee to curb the unfavourable characteristics.

Blending allows an increased flavour potential and when used correctly, can mould even the best coffees in the world to be “better” and exactly what the consumer or brewer wants. However, at the specialty level, coffees are often so exceptional that they do not need to be altered and in these cases the consumer/brewer is usually after getting the most out of that particular coffee and pushing its potential, not manipulating it with other coffees. So in specialty coffee, blends are less common.

Why are some of us “Anti-Blend”?

For the purist specialty coffee consumer who is looking for a flavour experience that translates coffee processing, origin, terroir, varietal and producer nuance, it’s quite simply the fact that a blend just doesn’t cater to this. When we are blending multiple coffees together, the consumer can’t taste the nuances of each coffee in the same way as drinking it as a single origin. Blending can certainly be another way to explore and push the boundaries of coffee flavour. As an example, and perhaps a challenge, if you’ve got a coffee at home that you really enjoy most characteristics of, try and blend it with a coffee that has great characteristics in the areas the other might let you down. See if you could improve an already enjoyable coffee even more.

{Ed's Note: I have done this successfully at home and the results have been delicious! Give it a bash!}

If we are looking at the subject of blending with a hyper critical eye, it can be argued that “everything is a blend”. Scott Rao, revered coffee pro, writes in his blog “At the farm level, cherry from various types of coffee trees may be blended and harvested together. At the dry mill, coffee in parchment or seed form, from numerous varieties or farms, may be blended at various steps to produce a lot with a single marketing name. A roaster may blend several coffees before or after roasting. A barista may combine multiple coffees to make a filter coffee or espresso. In a sense, almost everything is a blend, even coffees called “single origin.”

Blending is an interesting way to explore coffee that has perhaps been hindered by its unfortunate reputation in specialty circles.